Il nostro sguardo a Lisbona per Alkantara Festival, rassegna internazionale nata nel 1993, oggi con la direzione artistica di Carla Nobre Sousa e David Cabecinha. Un festival dalla vocazione spiccatamente internazionale che punta lo sguardo sul dialogo fra le identità della scena contemporanea e sulla crisi ambientale della nostra epoca.

English version below

Accade nella velocità delle nostre vite che si entri nella città da porte inaspettate. Metro, bus, aereo, bus, taxi – e d’improvviso il buio di una sala teatrale. Siamo stati a Lisbona per il Festival Alkantara, catapultati al principiare di un fine settimana di novembre nella black box del Teatro do Bairro Alto. Prima dello spettacolo si deposita appena l’impressione di essere in un luogo internazionale, costruito da un sistema di segni che ci capita di intercettare anche in certi festival italiani, dove nasce una comunità temporanea di artist*, curatori e curatrici, ma anche DJ e clubbers, intorno a momenti spesso informali o partecipativi come workshop, dj-set e talk. Una sorta di international style del nostro mondo, un vocabolario comune di temi, immaginari, modalità intermediali – forse persino modi di costituirsi pubblico, di vestirsi da spettatore. Sarebbe bello catalogare le convenzioni grafiche, l’immagine coordinata scelta dai festival di arti performative, come i nomi e i titoli stanno in pagina: sporcati, esplosi, fusi, sfocati, diluiti, spezzati. La grafica disegna città in ebollizione, sospese fra l’ipoteca tardo-capitalista di un disastro annunciato e un futuro necessario oltre la specie. Seduti insomma sul suolo di un territorio fluido, che nella perfetta indefinitezza della black-box trova una cassa di risonanza naturale.

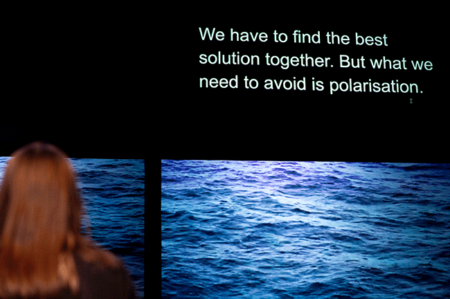

Così appare altrettanto naturale la postura di Silke Huysmans e Hannes Dereere in Out of the Blue. Seduti alla scrivania, spalle a chi guarda, i volti illuminati dagli aloni bluastri dei loro Macbook e da una quinta di monitor da 60”: sono l’ultimo lembo di pubblico, in parte spettatori di fronte al loro stesso lavoro e di fronte alla performatività della tecnologia convocata. La bidismensionalità di quegli schermi è un’illusione, come il pelo dell’acqua: la memoria virtuale è un labirinto di file che Huysmans e Dereere svoltolano per portarci nella profondità dell’Oceano Pacifico, lì dove non c’è luce come in un’altra, remota black box. “We know more about the surface of the moon than we do about the bottom of the ocean”. Abbiamo già sentito qualche volta, ma chissà dove, questo incipit che segna le coordinate assiali della performance: la vertigine dell’esplorazione e il piano della conoscenza umana. Anche le profondità del paesaggio marino possono diventare un territorio da colonizzare. Senza proferire parola e senza alcuna coreografia che non sia quella della mani sulle loro tastiere, il duo fiammingo ci porta a largo di un fermo immagine geometricamente perfetto. Tre navi ferme al centro della distesa blu. Una appartiene alla Deme-Gsr, company belga dedita all’estrazione di risorse minerarie suboceaniche; la seconda accoglie biolog* e geolog* marin* facenti capo all’ISA (international seabed authority, ente riconosciuto dall’Onu e preposto alla salvaguardia dei fondali); la terza si chiama Rainbow Warrior e sul suo scafo campeggia il blasone di Green Peace.

Tre navi, tre personaggi e nei loro ventri le voci con cui Huysmans e Dereere hanno interloquito negli ultimi tre anni, mentre conducevano da casa, online, la loro ricerca sul tema, nata durante la pandemia a suggello di una trilogia sul tema dell’escavazione delle risorse minerarie. Le testimonianze audio e i dati raccolti intessono una drammaturgia nitida, scandita da un’operazione di selezione e apertura di file, così che la modalità di costruzione del discorso segue le logiche di accumulo e riorganizzazione del sapere che tutti esperiamo nella nostra quotidianità digitale. Il punto di vista dei due non propende per una delle parti in causa. Oltre alla facile retorica del rifiuto verso ogni forma di sfruttamento pionieristico delle risorse ambientali, la testimonianza della Deme-Gsr è posta sullo stesso piano del rifiuto radicale di Green peace e della cauta raccolta dati dell* scienziat*. Se le operazioni di sondaggio e estrazione compromettono l’equilibrio di un ecosistema ancora insondato, i depositi sottomarini, d’altro canto, sono cruciali per il fabbisogno della filiera elettrica dell’automotive. In un avvitamento di argomenti e di retoriche il cui perno dovrebbe essere la scienza (la terza nave), il disastro ambientale appare dunque una variabile fissa. Il paradosso e l’impotenza declinano in uno stato d’animo profondamente condiviso, un senso di malinconia creaturale che è l’altro significato del titolo (out of the blue significa all’improvviso, ma being blue è anche sentirsi tristi).

Nell’impossibilità di tracciare una strada tuttavia improcrastinabile, finiamo per sentirci nei corpi diafani e fluorescenti di quelle creature abissali, nel loro movimento magnificamente arbitrario e fragile, fluttuante sui monitor. Qui l’opera acquista il tono di un neo-neoromanticismo in cui il tessuto documentario (fatto di report, ma anche di un’interessante analisi sulla politica comunicativa della grande coorporation e di Greenpeace) si smaglia su un campo di parole battute a tastiera, materia lirica che mette in vibrazione anche l’accurata mole di dati. Il richiamo ultimo di una metodologia di scrittura così rigoroso è dunque il nostro corpo, interpellato prima di fronte al dilemma etico ed economico, poi come sostanza a rischio di estinzione, tanto per la congiuntura storica che per un ancestrale senso di finitudine. Si fa eco, questa corporeità marina senza tempo, enigmatica eppure profondamente antropomorfica, con quella della Mami Wata, la sirena della mitologia centrafricana che anima Mascarades di Betty Tchomanga, performer e coreografa afrosdiscendente. La creatura ibrida, seducente mostruosità che attraversa ogni mitologia, approda su un piccolo piedistallo drappeggiato da una velina argentea. Uno spesso impermeabile trasparente copre senza coprire il corpo della performer, rimandando alla minaccia di un alluvione o all’emersione da un pericoloso liquido fluorescente. La sirena è una figura dell’alterità, ma qui lo spavento non è solo quello dell’osservatore, quanto quello reciproco della protagonista, secondo uno schema in crescendo che s-maschera la dialettica del potere alla base del guardare stesso. Ci troviamo anelanti di fronte al manifestarsi di un’entità ctonia, sessuale, che prende forma al ritmo convulso di un beat brutale, dalle sonorità afro e techno, lacerato dal grido-canto che seduce terrorizzando. Il processo di somatizzazione di Tchomanga oscilla dunque fra desiderio e rifiuto, mostrando la violenza del mito sul corpo femminile e l’emergere di una strategia di resistenza all’interno di quella dialettica.

Un linguaggio-lignaggio della lotta messo in scena come conquista, come materia scavata dal magma mostruoso dell’essere-sirena, che progredisce dal fondale al proscenio, finendo per tenderci letteralmente la mano che alcuni del pubblico, più decisi, stringono. Dal grido si produce la parola che affiora, sul finale, in una frase che evoca un epigrafico, necessario programma politico: “and i shall just be interested in my darling sister’s eyes”. Attraverso un’alleanza di occhi e di mani comincia anche Sacrifice While Lost In Salted Earth, del coreografo iraniano Hooman Sharifi, con 8 performer che si confondono nella platea del Teatro Sâo Luiz, presentandosi un* ad un* e scambiando poche, calorose parole con gli spettatori. Le sacre du printemp di Stravinkji diventa qui materia per una lettura corale del significato del sacrificio oggi: Sharifi ha riunito sette danzatori e danzatrici iranian* proprio a partire dalla celebre danza sacrificale. Due tempi performativi, una sequenza di assoli e una parte corale, riflettono il processo creativo in cui il coreografo ha lasciato lavorare ciascun* performer sul tema da remoto, per poi inviare a tutt* un assolo della coreografia, interpretato da lui stesso. Il risultato è una diffrazione di gesti, fra imitazione e intepretazione, performance e rito collettivo. La lingua costruita sulla musica de Le Sacre, eseguita in scena da un suonatore di tanbur (strumento a corde della tradizione persiana) in una commovente versione scarnificata della partitura, trova con immediatezza un registro universale. Proibita in patria, questa danza è essa stessa il sacrificio esule di chi la vive, tanto di più in queste settimane, mentre riceviamo sporadiche notizie delle proteste animate soprattutto dalle donne iraniane. Torniamo al prologo dello spettacolo, mentre parliamo con Masoumeh Jalalieh, una delle performer. Masoumeh chiede il mio nome, mi dice che lo trova bello, poi aggiunge che sarà presto in Italia per una performance. Prima dello spettacolo si deposita appena l’impressione di essere in un luogo internazionale, o forse universale.

Andrea Zangari

ENGLISH VERSION

It is possible that in our swift lives one enters the city through unexpected doors. Metro, bus, plane, bus, taxi and eventually the darkness of a theater hall. We were in Lisbon at the Alkantara Festival, catapulted at the beginning of a November weekend into the black box of the Teatro do Bairro Alto. Before the show, the impression of being in an international landscape barely settles, something built by a system of signs that we also happen to intercept in certain Italian festivals, where a temporary community of artists, curators, but also DJs and clubbers, gathers at often informal or participatory moments such as workshops, dj-sets and talks. A sort of international style of our world, a common vocabulary of themes, imaginaries, practices – perhaps even ways of constituting oneself as an audience, of dressing up as a spectator. It would be nice to catalogue the graphic conventions, the coordinated image chosen by performing arts festivals. How do the names and titles lay on the page? Dirtied, exploded, merged, blurred, diluted, broken. The graphic depicts boiling cities, suspended between the late-capitalist prophecy of a disaster and a necessary future beyond the species. In short, sitting on the ground of a fluid territory, which perfectly echoes in the indefiniteness of the black box.

On such ground, the posture of Silke Huysmans and Hannes Dereere in Out of the Blue appears a natural one. Sitting at the desk, giving us their backs with their faces illuminated by the bluish halos of their Macbooks and by a backdrop of 60” monitors: they are the last strip of the public, somehow spectators in front of their own work and the performativity of the technology on stage. The two-dimensionality of those screens is an illusion, like the surface of the water: the virtual memory is a labyrinth of files that Huysmans and Dereere unwind to take us to the depths of the Pacific Ocean, where there is no light as in a remote black box. “We know more about the surface of the moon than we do about the bottom of the ocean”. We have already heard a few times, but who knows where, this incipit that marks the axial coordinates of the performance: the vertigo of exploration and the land of human knowledge. Even the depths of the marine landscape can be a territory to colonize. Without saying a word and without any choreography other than that of the hands on their keyboards, the Flemish duo takes us off the waters, in a geometrically perfect still image: three ships stationing in the center of the blue blanket. One belongs to Deme-Gsr, a Belgian sea-mining company interested in suboceanic mineral resources; the second welcomes marine biologists and geologists from the ISA (international seabed authority, recognized by the UN and in charge of seabed safeguarding); the third is called Rainbow Warrior and the shield of GreenPeace stands out on her hull.

Three ships, three characters and the voices in their bellies with which Huysmans and Dereere have conversed over the last three years, while conducting their online research on the topic from home, a research born during the pandemic to seal their mining trilogy. The audio testimonies and the collected data weave a clear dramaturgy, punctuated by an operation of selecting and opening files, so that the method of the discourse follows the logic of knowledge accumulation and organisation that we all experience in our digital everyday life. The point of view of the two does not favour one of the parties involved. Beyond any easy rhetoric of refusal of any form of pioneering exploitation, the testimony of Deme-Gsr is placed on the same level as the radical refusal of GreenPeace and the cautious data collection of the scientist. If drilling and extraction compromise the balance of an ecosystem that is still unexplored, on the other hand submarine deposits are crucial for the needs of the automotive electric supply chain. In a twisting of arguments whose pivot should be science (the third ship), the environmental disaster therefore appears to be a fixed variable. Paradox and impotence decline in a deeply shared state of mind, a sense of creatural melancholy which is the metaphorical meaning of the title.

At the fork between the need and the impossibility of tracing a path, we end up feeling ourselves in the diaphanous and fluorescent bodies of those abysmal creatures, in their magnificently arbitrary and fragile movement, floating on the monitors. Here the work acquires the tone of a neo-neo-romanticism in which the documentary fabric (made up of reports, but also of an interesting analysis of the communication policy of the large corporation and Greenpeace) is unraveled on a field of keyboarded words, lyrical material that sets in vibration even the accurate mass of gathered data. The ultimate appeal of such a rigorous writing methodology is therefore our body, first questioned in the face of the ethical and economic dilemma, then as a substance at risk of extinction, both for the historical situation and for an ancestral sense of finitude. This timeless marine corporeity, enigmatic yet profoundly anthropomorphic, echoes with that of Mami Wata, the siren of Central African mythology which animates Mascarades by Betty Tchomanga, Afro-descendant performer and choreographer. The hybrid creature, a seductive monstrosity that runs through every mythology, lands on a small pedestal draped in silver tissue. A thick transparent raincoat covers without covering the performer’s body, referring to the threat of a flood or the emergence from a dangerous fluorescent liquid. The siren is a figure of otherness, but here the fear is not only that of the observer, but the reciprocal one of the protagonist, according to a growing pattern that unmasks the dialectic of power at the basis of the act of looking itself. We find ourselves yearning for the manifestation of a chthonic, sexual entity that takes shape in the convulsive rhythm of a brutal beat, with Afro and techno sounds, torn apart by the siren’s cry-song that seduces and terrifies. Tchomanga’s process of somatization therefore oscillates between desire and refusal, showing the violence of the myth (co-performed by our glance on her) on the female body and the emergence of a strategy of resistance within that dialectic.

This language\lineage of fight is staged as a conquest, as material excavated from the monstrous magma of the siren-being, which progresses from the backdrop to the proscenium and ends up extending her and which some of the audience, more determined, shakes. From the cry comes the word that emerges, at the end, in a sentence that evokes an epigraphic, necessary political program: “and I shall only be interested in my dear sister’s eyes”. Sacrifice While Lost In Salted Earth, by the Iranian choreographer Hooman Sharifi, also begins through an alliance of eyes and hands, with the eight performers who blend into the audience of the Teatro Sâo Luiz. They introduce themselves one to one and exchange a few, warm talks with viewers. Stravinkji’s Le sacre du printemp here gives matter for a choral reading of the meaning of sacrifice today: Sharifi has brought together seven Iranian dancers precisely starting from the famous sacrificial dance. Two performative times, a sequence of solos and a choral part, reflect the creative process in which the choreographer let each performer work on the theme remotely, to then send them all a solo of the choreography, interpreted by himself. The result is a diffraction of gestures, between imitation and interpretation, performance and collective ritual. The language built on the music of Le Sacre, performed on stage by a tanbour player (a stringed instrument of the Persian tradition) in a moving stripped-down version of the score, immediately strikes a universal register. Forbidden at home, this dance is itself the exiled sacrifice of those who live it, especially in recent weeks, while we receive sporadic news of the protests animated above all by Iranian women. Let’s go back to the prologue of the show, as we talk to Masoumeh Jalalieh, one of the performers. Masoumeh asks my name, she tells me she finds it beautiful, then she adds that she will be in Italy soon for a performance. Before the show, the impression of being in an international landscape barely settles, or perhaps universal.

Alkantara Festival, Lisbona – novembre 2022

OUT OF THE BLUE

di e con Silke Huysmans & Hannes Dereere

drammaturgia Dries Douibi

occhio esterno Pol Heyvaert

sound design Lieven Dousselaere

produzione CAMPO

coproduzione Beursschouwburg (Brussels), Bunker-Mladi Levi (Ljubljana), De Brakke Grond (Amsterdam), Kunstenfestivaldesarts (Brussels), Noorderzon Festival (Groningen), PACT Zollverein (Essen), Théâtre de la Ville (Paris), Zürcher Theater Spektakel

MASCARADE

di e con Betty Tchomanga

light design Eduardo Abdala

sound design Stéphane Monteiro

outside look Dalila Khatir e Emma Tricard

consulente vocale Dalila Khatir

SACRIFICE WHILE LOST IN SALTED EARTH

coreografia, regia e luci Hooman Sharifi

con Ali Moini, Tara Fatehi Irani, Roza Moshtagi, Ehsan Hemat,

Armin Hokmi, Sorour Darabi, Kiana Rezvani, Hooman Sharifi

musica live Arash Moradi

produzione Rikke Baewert