Leggi questo articolo in italiano

Leggi questo articolo in italiano

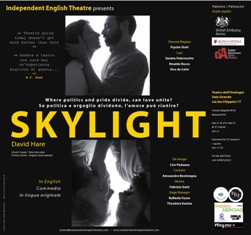

It’s hard times. Especially for independent venues and artists, which base their very survival on the audience turnout, made difficult by the enormous and not always exciting competition of 81 other playhouses. To present Skylight,, the award-winning play by established British playwright David Hare in its “most original” version, that is to say with no Italian translation, drastically narrows the field and thus the number of spectators. Result: unfortunately the third run counts just eight people in the stalls of the “multiplex off playhouse” Teatro dell’Orologio in Rome. Interesting and important, beyond the outspoken promotional intent of British Embassy’s support, is the work of Independent English Theatre company, voted to a philological and up to date approach in giving back to foreign audience a mirror of contemporary British playwriting.

Ciro Paduano’s set design recreates with hyperrealistic taste a typical British interior full of every small detail familiar to anyone has ever entered a flat in the dimmed winter light of London. No sponges on the sink, but a long scrub brush, close at hand a jar of HP sauce, tea is necessairly PG branded, orange plastic bags remind of Sainsbury’s. We’re in Kyra’s house (Sandra Paternostro), teacher in a poor East London high school, who during the same night receives a visit from young Edward (Vico De Carle), complaining about her disappearance, and from his father Tom (Rinaldo Rocco), a rich restaurateur and ex-lover of her. The decease of Tom’s wife Alice, who had discovered the betrayal forcing Kyra to move out from the family, makes now re-emerge a bitter past.

The style of the text is common to many contemporary British plays: unity of time and space, a precise socio-political context and a river of dialogues flowing as fast and steeply as possible, spit out without giving the way to melodrama and dotting the pace with pauses to piece the thoughts together. If we often complain about the verbosity of certain writing it’s because we believe that the word on stage should instead preserve its own essentiality. Which is not necessairily reached rationing the lines. Here we find the opposite strategy, that covers the action with a verbal and gestural plateau which rarely admits any latency, so that the key sentences and movements (few, by the way) can emerge in force of their very supremacy, almost under the form of a natural selection.

The three skilled actors, with a fair prominence of Paternostro and Rocco, put together the story of a love triangle without ever “putting it on stage”, since Psyche Stott‘s direction relegates it in a past made out of dead leaves, of repressed grief, whose very emotional firepower is preserved by the exposition of a significant sense of absence. The realtionship between Tom and Kyra, revived by a sudden backflame, gets estinguished again by the cold shivers of memory and by an overwhelming social divarication between the flashy individualism of Chelsea upper class and a cultural militancy rediscovered in East Ham social gutters.

In a jungle of very realistic and meticulous details made of many tiny casual gestures, from tidying the living room to emblematic tomato-sauced spaghetti really (as the text asks) cooked on stage, certain sampled sounds (doorbell ringing, car door slamming and ambulance waving down the street) can at a first sight appear out of tune. Nevertheless the poetical core might be just there, in that micro-universe of close reproduction of reality, that, set against the cold mechanic of the sounds coming from “outside”, builds an ultimate bulwark of truth in a world ruled by lies and pretence.

This might also explain the choice of leaving the backwall naked, showing a dark and uninhabited backstage. That’s why is so bloody cold in there.

Sergio Lo Gatto