- Belarus Free Theatre – Being Harold Pinter

There is a lot of talk about value crisis, about cultural decadence, about institutions which rob the citizens of the resources needed to develop an artistic or research project. And everybody gets indignant, everybody lines up, everybody hammers away at the very principle, feeling packed in a cage of powerlessness. But with regard to Western world, we are pretty much talking about strictly economic impediments. Politics surely contributes, atrophying the interest towards education and expressive urgencies, but still it is a finance-oriented politics. Nevertheless, we often complain about a lack of freedom. Freedom. We are sure that we do know what this word means. But we don’t.

Prospettiva Festival in Turin hosted one of the most unique artistic realities nowadays, real “strangers in their own country” (which was the theme of the Festival 2011 edition). Formed in 2005, Belarus Free Theatre is a Belarusian group committed in a strenuous intellectual fight against the regime of cultural repression led by prime minister Aleksandr Lukashenko, the last one still alive after Soviet Union’s collapse. In this country press and artistic productions are literally “owned” by the government, which enforces a complete censorship upon them.

Being Harold Pinter puts some short plays by the British playwright together with excerpts of the lecture he held during the Nobel Prize Ceremony in Stockholm in 2005. The play had premiered in 2007 in Leeds in the frame of the conference Artist and Citizen: 50 Years of Performing Pinter, which Pinter himself had attended. That occasion had in fact been an international turning point for BFT, brought up to the whole Occident’s attention as the most severe yet vivid cultural emergency nowadays.

At the time of the award ceremony, Pinter was already ill and unable to claim the prize in person. The 46 minutes long speech was recorded in a Channel 4 studio in London with the title Art, Truth and Politics [go to the complete text] and then projected on a screen in front of the Stockholm audience. In those words stays all Pinter’s theatre, for too long adored and promoted as a theatre of emotions, a psychological theatre, a private theatre, and by those very words reclaimed as a strictly political one. The playwright chronicles some of the themes approached by his plays, he presents the writer’s extraordinary creative process as it was the unexpected effect of an involuntary muscle, the primary instinct of an urgency: to produce truth.

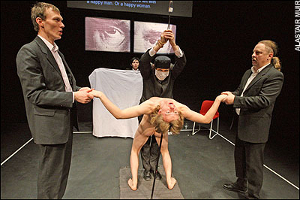

BFT uses simple and clean means. The scene is a white square whose angles are delimited by four stools; on the backcloth, divided in two halves, hangs a close-up portrait of Pinter’s eyes. The writer’s speech is turned into a stream of consciousness, through its texture the explosive strength of characters unravels: rarefied atmospheres, the cutting edge of the lines, all emphasized by the essential nature of scenery and acting, never trying to create a sensation, always observing a great cold-shoulder.

However much in the last few years the international intellectual community has been openly lining up with the company and plenty of mobilizations and protests currently support its cause, still the group lives and works in whole illegality. If the first performances took place in private houses around Minsk suburbs, now BFT’s shows are also programmed by big European and American theatres. The time of police’s armed break-ins and mass arrests seems so far and the latest news, spread by BFT themselves during a public meeting the day after the show in Turin, are comforting. The seek of political asylum forwarded to British government, in good standing, will have as a first outcome the participation in the cultural activities framed by 2012 London Olympics: their King Lear will be one of the 37 shows produced by Globe Theatre in 37 different languages.

Being Harold Pinter is obviously a proof of the greatness of the Nobel winner; yet the play flies higher. The three subjects underlined by the speech’s title – art, truth and politics – arise as sacred monoliths to testify a paradigm of the Belarusian company, flags of that extraordinary yet terrible phenomenon which is the deprivation of freedom. Then the show makes a real (in every possible meaning) sense when, in the middle of Pinter’s thought – all in all reverberating a middle-class intellectual idleness purposely wrapped for the Swedish audience – the violence of the chronicle explodes. Coming directly from a bitterly ironic moment, almost comic (Mountain Language), the dark falls: each actor points a flashlight at his own hooded face. As they were sharing the same dream, short memories of the victims of the repression reflect like fragments of a mass nightmare. The last words of Nobel speech recite:

«When we look into a mirror we think the image that confronts us is accurate. But move a millimetre and the image changes. We are actually looking at a never-ending range of reflections. But sometimes a writer has to smash the mirror – for it is on the other side of that mirror that the truth stares at us.I believe that despite the enormous odds which exist, unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination, as citizens, to define the real truth of our lives and our societies is a crucial obligation which devolves upon us all. It is in fact mandatory. If such a determination is not embodied in our political vision we have no hope of restoring what is so nearly lost to us – the dignity of man». Period.

Sergio Lo Gatto