Teatro e Critica diventa internazionale. Con il contenuto che segue inauguriamo una nuova sezione della nostra webzine, interamente in inglese. Gli articoli ritenuti “di interesse globale” verranno tradotti in inglese in modo da offrire una panoramica del teatro visto da qui (anche) ai lettori che cliccano dall’estero. Ambizione di questa sezione è anche quella di includere contenuti provenienti da altri paesi. A questo proposito, tutti voi che seguite il teatro fuori dall’Italia siete invitati a sottoporre articoli e idee al nostro indirizzo di redazione: redazione@teatroecritica.net. Buona lettura!

Teatro e Critica goes international. The following feature launches a new section of our web-magazine, fully written in English. The “global-interest” articles will be translated in English in order to offer an overview of theater “seen from here” (also) to the readers clicking from abroad. Aim of this new section is also to include features coming from other countries. At this purpose all of you who follow and keep up with theater from outside Italy are invited to submit features and ideas to our editorial e-mail address: redazione@teatroecritica.net. Enjoy!

Leggi l’articolo originale in italiano

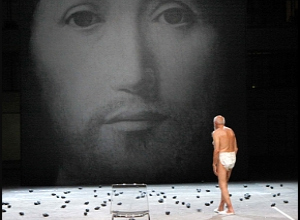

- Sur le concept du visage du fils de Dieu

Extremists. If they didn’t exist we’d have to invent them. Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio/Romeo Castellucci went on stage at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris with Sur le concept du visage du fils de Dieu, an accurate investigation on the hazard of representation and the limits of the sensibility. When the show premiered in Italy in 2010, nobody ever dreamed about correlating Antonello da Messina’s portrait of Jesus Christ with the scene of a man brutalized by incontinence. An incontinence which conceptually represents the most evident symptom of an imminent death. In the mutual care between men stays the very matter of the show, which condenses the concept of “belonging to the human chain” putting the actors in a distressing blank space.

From a huge painted canvas, Christ watches over this scene. In the ending, a sort of ink flow (reminding pages and pages written along the centuries) leads to the break-up of that very icon, hinting at the loss of spirituality. During the Paris rerun and for many days from that moment on, a group of Catholic extremists has been boycotting the performance chaining themselves to the gates in front of the entrances and obstructing the access throwing smoke and stinky bombs; even pouring fish and motor oil on the head of the audience sitting in the stalls. Some of them gathered around the stage to rave Latin prayers as a sort of exorcism against an apparently evident blasphemy. Among the fundamentalists, the Catholic ones have an undeniable characteristic: the theatrical nature of their actions. Centuries of sung liturgies and gatherings established a very tight relationship with the stage, to the point that separating a mass from a mise en scène has become quite an accomplishment.

The Catholic dogma remained constantly present in the Western world on a peculiarly formal level; to follow the doctrine is a bit like to rerun a show which has been performed so many times to end up going automatically. In that very action stays a sort of self-martirization, a conceptual and practical attitude which emulates the martyrs of the past and is almost never able to enfranchise the dominant thought which bases – no intention to judge the effects – the Western culture, constantly putting on stage that “persecuted person syndrome” typical of those religions of sorrow and sin.

Passing through a congenital marginality, in these times theater seems rather undergoing a moment of celebrity. Before Castellucci in France, the protest had beat on Rodrigo García, found guilty of presumed torture on animals during his show Muerte y reencarnation en un cowboy at Venice Biennale [go to the article – in Italian]. In both cases, as a sign launched when the news breaks into the normal order of events, has been called the police.

It’s so unsettling that certain artistic excellencies can find a space on the newspaper only in such extraordinary cases. Yet this is the consequence of giving way to sensationalism, which here is the one and only guilty.

It’s not just chance that, according to the news, besides Catholics there were extreme right wing groups: rejected by cultural evolution, they are unable to find a better way to enter a theatre and make the people talk about them. They end up with promoting their own rules over artistic expression, converting their unbearable sense of cultural ostracism into a brutal protest. Some of them, as political leaders, try to give voice to that feeling by subtracting a culture rather than proposing an alternative one. This might as well show the necessity of underlining a personal position exploiting other people’s stages. In the presence of a dogma, with no chance to be discussed, a cultural discourse could never exist.

Therefore the challenge is elsewhere: may they bring their indignation on the stage, may they turn it into art. Then we will treat them as equals. Must art be thrown into crisis? Then let’s find an appropriate place for this: the scene itself, rather than a pulpit or a podium.

Simone Nebbia

[translated by Sergio Lo Gatto]

[…] texte (en anglais) de Simone Nebbia, du magazine italien TeatroEcritica, qui aborde la question […]